Tagged: movie

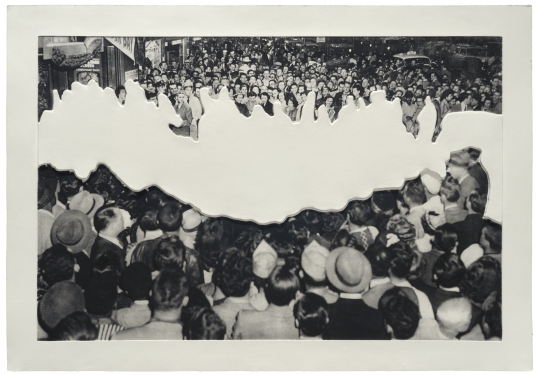

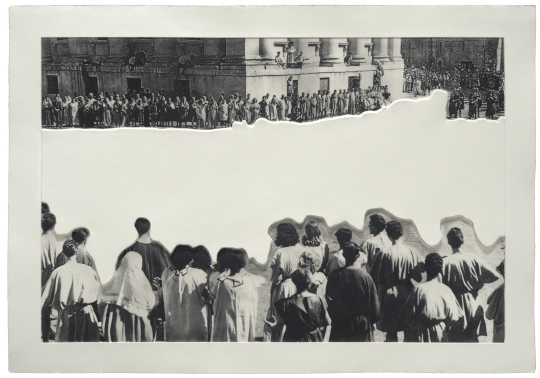

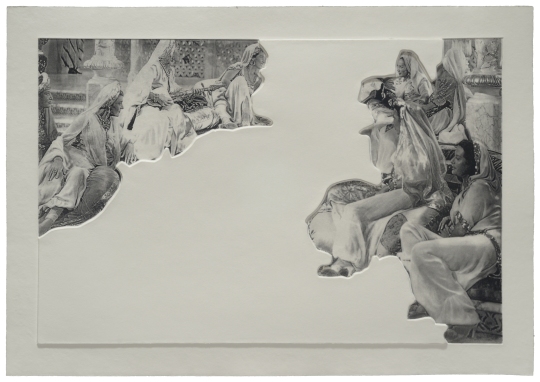

Baldessari’s Crowds With Shape of Reason Missing (2012)

In John Baldessari’s Crowds with Shape of Reason Missing (2012), individuals gather together in formation or haphazardly while captivated by the unknown – a somewhat silly white blob. The artist removes the predominant subject of the photographic image and replaces it with the nondescript form. Baldessari chose vintage movie stills that seem at once recognizable and yet unfamiliar. With the main subject gone, the focal point is unclear, which leads us to scan the faces and actions of the crowds: soldiers, onlookers, community members, and harem girls. The viewer then focuses on the reactionary rather than the primary. The artist elucidates: “Erasure is a kind of gap. The imagery that our culture produces tends to have its own coherence and legibility, and the set of expectations that comes with that legibility can be disrupted through visual interventions.” Baldessari effectively transfixes us by barring us from the action; he forces us to reconsider the now voided narrative.

cul-de-sac

contempt

Josef Müller-Brockmann

realidades rurales y ricas

“La vida tiene sus maneras de enseñarnos.”[i]

Director Alfonso Cuarón and cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki nos enseñan through peripheral incidents and characters, well-framed shots, and precise, penetrating dialogue. In their “three-way love romp on wheels,”[ii] we face a serious critique of how rich Mexico and poor Mexico coexist. We are presented with Tenoch Iturbide, the son of a high-ranking, corrupt political official, and Julio Zapata, a leftist from a lower middle class family. The over-sexed, underdeveloped male duo, just out of high school, are joined by the attractive, troubled, and enigmatic Luisa Cortés, a twenty-something Spaniard grappling with her husband’s infidelity and cancer. An unseen, omniscient narrator accompanies the trio with an unapologetic frankness in its dose of severity and social criticism. Together, they head out of Mexico City, making their way toward a supposedly fictional beach paradise. Along the way, seduction, argument, and the disparity between their unchallenged luxury and the harsh actuality of the surrounding poverty ensue. Alfonso Cuarón’s Y tu mamá también candidly denounces Mexico’s political savagery, vicious class divisions and inane machismo that sabotage any hope of social progress.

In the stride toward social reform, the merciless government acts as a barricade, sometimes quite literally. We learn quickly that Tenoch’s father is Secretary of State, as a part of the ruling party in Mexico at the time: the PRI Purple, the presidential party for the previous 71 years. He gave his son Tenoch an Aztec name to appear as though he was a man of the people. He was in fact, however, linked to a scandal, involving the sale of contaminated food to the poor. Even when Luisa questions Tenoch about whether his father is honest, he laughs sneeringly, asserting to her and the audience that he is quite the opposite. Closely associated with the political leadership of the country is its legal enforcers, who appear several times in the course of the film as devious, ominous, and overbearing. The ever-armed federales are everywhere: they conduct police inspections, targeting poor laborers and bystanders. Whatever goods are left with the campesinos are soon stolen or taken away. It becomes apparent that Mexico’s educated, privileged ruling class, exerts its dominion forcefully in order to profit from the poor. Its ambition is roused financially; through the globalization of its assets or the squandering of its people’s money.

In the stride toward social reform, the merciless government acts as a barricade, sometimes quite literally. We learn quickly that Tenoch’s father is Secretary of State, as a part of the ruling party in Mexico at the time: the PRI Purple, the presidential party for the previous 71 years. He gave his son Tenoch an Aztec name to appear as though he was a man of the people. He was in fact, however, linked to a scandal, involving the sale of contaminated food to the poor. Even when Luisa questions Tenoch about whether his father is honest, he laughs sneeringly, asserting to her and the audience that he is quite the opposite. Closely associated with the political leadership of the country is its legal enforcers, who appear several times in the course of the film as devious, ominous, and overbearing. The ever-armed federales are everywhere: they conduct police inspections, targeting poor laborers and bystanders. Whatever goods are left with the campesinos are soon stolen or taken away. It becomes apparent that Mexico’s educated, privileged ruling class, exerts its dominion forcefully in order to profit from the poor. Its ambition is roused financially; through the globalization of its assets or the squandering of its people’s money.

At constant juxtaposition are the echelons of the Mexican caste system. Cuarón highlights the most extremes: the upper elite and the absolute indigent. Tenoch and Julio, so hormonally charged up and narcissistic, are utterly unaware of the peasants who are in their service. Servants in Y tu mamá también are also omnipresent. They are depicted with quiet, unpretentious respect. Tenoch’s family hires help. Bodyguards almost outnumber guests at the monotonous rodeo wedding. The camera guides us away from the party: a waitress brings food to a crowd of unenthusiastic chauffeurs. Even away from their privileged lives in Mexico City, they act like tourists, waiting to be waited on. The young boys unconsciously prop up every conservative system they claim to hate. They strive to be these anti-aristocrat rebels, and yet in their blind-sighted self-centeredness, they completely ignore their backdrop. One drunken night at a poor fisherman’s family restaurant, these rude jackasses brazenly boast about vulgar sexual experiences in front of simple townspeople. We wince at their unabashed indiscretion. Their ignorance epitomizes the indifference of their society — the society that chooses to disregard its domestic support. It is for this reason that the grave gap between the opulent and the austere is so obvious — so monumental.

“Play with babies; you’ll end up washing diapers,” Luisa mutters, stomping off along the road when she’s had enough of the boys’ bickering. The juvenile machos constantly try to out-seduce, out-boast, out-last each other. Tenoch and Julio’s entire friendship stems off of strong pride: machismo, Mexican Spanish for an aggressive bravado. Their limitless competitiveness, in the end, proves their fallibility. In their summer of boredom, they even attempt to out-masturbate one another! Swimming, sexual encounters, social status, even girlfriends are fair game in their cock-fight-like contests. However, this stubborn, head-strong, proud mindset plagues Mexican culture. As archetypical examples, Tenoch and Julio, along with their extreme male chauvinism, parade around, too pompous to pay attention to what really needs tending to.

“Play with babies; you’ll end up washing diapers,” Luisa mutters, stomping off along the road when she’s had enough of the boys’ bickering. The juvenile machos constantly try to out-seduce, out-boast, out-last each other. Tenoch and Julio’s entire friendship stems off of strong pride: machismo, Mexican Spanish for an aggressive bravado. Their limitless competitiveness, in the end, proves their fallibility. In their summer of boredom, they even attempt to out-masturbate one another! Swimming, sexual encounters, social status, even girlfriends are fair game in their cock-fight-like contests. However, this stubborn, head-strong, proud mindset plagues Mexican culture. As archetypical examples, Tenoch and Julio, along with their extreme male chauvinism, parade around, too pompous to pay attention to what really needs tending to.

Prevalently, it is death that reinforces the unabashed boys’ shortcomings. As if sheltered from reality, Tenoch and Julio coast past harrowing and haunting car accidents, grave sites, and funeral processions. And still, even further, although puzzled by her solemn weeping, they never think to console Luisa, who is fated to die from the cancer that has overtaken her. They are foolish, naive children, pretending to be strong-minded men. They scheme, fret, and twist themselves into jealous knots around Luisa, not once focusing on the despair and misery in the Mexican landscape.

[i] “Y tu mamá también.” IMDb.com, Inc. The Internet Movie Database. (2001). <http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0245574/>.

[ii] Bradshaw, Peter. “Y Tu Mama Tambien.” guardian.co.uk. The Guardian New and Media Limited. (2002). <http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2002/apr/12/1>.